Background

Alexander the Great started his great endeavour either the last week of March or the first week of April 334BC.1Donald Engels's Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army discusses the reasons for this, namely: it would coincide with arriving in Persian lands when rations ran out, but crops were harvested.

The Macedonian army arrived at Sestus (a city on the Greek side of the Dardanelles) 20 days later, Arrian (I.11.3–5) reports and Donald Engels justifies in his book.

Arrian claims Alexander went to Troy whereas Parmenion took the army across the Dardenelles then to Arisbe; Diodorus agrees, but notes 60 triremes accompanied Alexander (XVII.17.2).

If organized well, it is entirely feasible the crossing took a few hours in the morning, which allows Parmenion to reach Arisbe by midday of the 22nd days of the expedition. Parmenion had to transport his men across about 2 kilometers of the Dardanelles with 160 triremes and "numerous other ships", which should take no more than a day. However, upon arriving at Sestos, it is likely the army rested a day, since horses need to rest one day every six days of marching. The alternative would be crossing the Dardanelles, and then resting, which would expose the army for a day (giving more time for Persians to organize an army to challenge the expeditionary force), which seems doubtful.

The Persian garrison of Arisbe may or may not have offered resistance, but it is likely they were able to send the message that some Greek invaders have arrived. Diodorus (XVII.18.2–4) reports the Persians did not act quickly enough to prevent the crossing but quickly organized a council of war.

The Greek mercenary general Memnon suggested to avoid fighting the invaders, and instead the Persians should destroy all crops within 30 miles. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see this plan would have complicated Alexander's plans greatly. But at the time, it sounded suicidal. Consequently, the council of war adopted the exact opposite plan: directly engage with Alexander's army at a favorable location — at Granicus river. Such, at least, is what Diodorus reports.

Diodorus tell us (XVII.19.1) Alexander learned of this then marched directly to Granicus. Arrian provides a more complete picture:

[I.12.6] From Ilium [Troy] Alexander came to Arisbe, where his entire force had encamped after crossing the Hellespont; and on the following day he came to Percote. On the next, passing by Lampsacus, he encamped near the river Practius, which flows from the Idaean mountains and discharges itself into the sea between the Hellespont and the Euxine Sea. Thence passing by the city of Colonae, he arrived at Hermotus. [7] He now sent scouts before the army under the command of Arayntas, son of Arrhabaeus, who had the squadron of the Companion cavalry which came from Apollonia, under the captain Socrates, son of Sathon, and four squadrons of what were called Prodromi (runners forward). In the march he despatched Panegorus, son of Lycagoras, one of the Companions, to take possession of the city of Priapus, which was surrendered by the inhabitants.

[8] The Persian generals were Arsames, Rheomithres, Petines, Niphates, and with them Spithridates, viceroy of Lydia and Ionia, and Arsites, governor of the Phrygia near the Hellespont. These had encamped near the city of Zeleia with the Persian cavalry and the Grecian mercenaries. [9] When they were holding a council about the state of affairs, it was reported to them that Alexander had crossed (the Hellespont).

[I.13.1] Meantime Alexander was advancing to the river Granicus, with his army arranged for battle, having drawn up his heavy-armed troops in a double phalanx, leading the cavalry on the wings, and having ordered that the baggage should follow in the rear. And Hegelochus at the head of the cavalry, who were armed with the long pike, and about 500 of the light-armed troops, was sent by him to reconnoitre the proceedings of the enemy. [2] When Alexander was not far from the river Granicus, some of his scouts rode up to him at full speed and announced that the Persians had taken up their position on the other side of the Granicus, drawn up ready for battle. Thereupon Alexander arranged all his army with the intention of fighting.

Engels computes the time it would take for Alexander's army to march along Arrian's route would take 4 days to arrive at Hermotus from Arisbe, which would be 5 days of marching since the army had rested. Remember, horses need rest every seventh day. It is one day of marching to arrive at Granicus from Hermotus.

This would make the battle of Granicus occur in early May 334 BC.

Where is Granicus, anyways?

The only river matching the classical description would be the Biga river. However, as Hammond noted in 1980, the course of the river was quite different 2300 years ago, probably a couple miles off. I'm not an expert on rivers, and at first this sounded insane. However, ancient historians noted severe earthquakes in the middle of the 5th century BC shifted the river's course, and there have been more earthquakes over the years, in addition to man-made pumps and dams. Consequently, the exact location is not the current location of the Biga river.

Archaelogists have used radio technology to confirm Hammond's claims, but this occurred between 2005–2007. If memory serves, the course of the river c.335BC is a couple miles from the current location of the river. The best estimates I have found is that it is somewhere between Çeşmealtı, Biga and Gümüşçay (the distance between these two towns is about 2.5 miles walking, so sayeth Google maps). There is a 2000 foot long ridge along the way, which is almost certainly where the battle was fought (approximately 40.304059N, 27.300118E).

Consequently, we do not know exactly the measurements of the river (its depth, width, steepness of banks) which are critical for analyzing the battle of Granicus. We are at the mercy of the ancient authorities.

When was the battle fought

Our two authorities disagree with the timing of the battle. Arrian claims Alexander marched to the river, then fought the battle on the same day. Diodorus claims Alexander marched to the river, then camped, and the next day fought the battle.

We can make an observation: astronomically speaking, the location of the Earth in the solar system would be the same in 334BC as in 2018AD. This is important because the first week of May would have sunset about 5:05–5:15pm and a waning moon: it would be too dark to fight a night battle.2The skeptical reader may hesitate to accept this argument on grounds that we don't know exactly where the battle took place. But we know where it took place somewhere within 1 degree of latitude and longitude (which is approximately 69 miles from the location proposed). This would change the time of sunset by less than a couple minutes, which doesn't change my underlying argument.

Further, there is a 28-year cycle to our calendar. That is to say, every 28 years, the calendar has the same sunrises and sunsets. More precisely, it's subdivided into 11 years, 11 years, 6 years sub-cycles. So 334 BC has the same calendar and sunrises and sunsets as 26 BC, or 3 AD, 1798 AD, 2018 AD.

This makes Arrian's description less plausible, but not implausible. Arrian does not tell us where Alexander was when his scouts informed him of the Persian army's location. If Alexander took a more leisurely march, say camping a half-day's march away from Granicus, then it is plausible to march to Granicus and then fighting the battle. But this raises the question: why was Alexander's army marching as if to battle before learning of the position of the persian army?

Also worth mentioning, if Alexander's army marched directly to Granicus, then it's getting alarmingly close to the point of exhausting the horses. Since cavalry plays a critical role in the Macedonian hammer-and-anvil, it seems likely Alexander rested an extra day along the march Arrian describes.

Army Strength

We have discussed Alexander's army before. Let's first analyze Persian army organization, estimate its size, then return to examine the Macedonian army's strength.

"Lost in translation" hypthesis

Classical authorities disagree drastically about the size of the Persian force. I have not seen any adequate explanation, but here's what makes sense to me. The old Persian word for "regiment" is Hazabaram [literally, "thousands"] which is a composite of hazara [the number 1000] and -bam turning the number into a noun (Sekunda and Chew's The Persian Army: 560–330BC point this out on page 5). When Diodorus (XVII.19.4) tell us about the thousand Bactrian cavalry, I interpret this as something lost in translation: it's really a regiment of Bactrian cavalry.

If this hypothesis is correct, then what seems most likely is Diodorus was correct in reporting 10 cavalry regiments (XVII.19.5) but incorrect in reporting "not fewer" than 100 regiments of infantry if by "infantry regiment" Diodorus meant something like a Taxeis. Arrian reports (I.14.4) the Persian force consisted of 20,000 cavalry and "slightly less" than 20,000 infantry, which would correspond to slightly less than 20 infantry regiments.

Is it feasible the Persians could have mustered 10,000 cavalry? Well, as Michael Taylor points out in his book Antiochus the Great, 10,000 cavalry is an enormous force by ancient standards

(pg.80).

If both Diodorus and Arrian err in mistranslating "regiment" because they are taking a stab (and failing) at translating the same source, then 2 of Arrian's regiment corresponds to 1 of Diodorus's regiment. This raises questions about how to reconcile the drastically different estimate of infantry. We could point out Diodorus has erred in calculations before. Another possibility is misidentification of tactical units as "regiment". A third possibility is these exaggerated numbers were in their original source, and it originally was a crude form of propaganda.

But if the mistranslation hypothesis is accurate, and relying on Arrian's estimate (I.16.2) that approximately 1 regiment of Persian cavalry fell, and further relying on the fact that Achaemenid cavalry were armored, then we should interpret Arrian's statement (I.16.7) that 300 suits of Persian armor were sent to Athen's acropylis reflects the estimate of slightly less than 300 horse in a Persian cavalry regiment. This corresponds to the Greek organization of a squadron of cavalry. (Coincidentally, Diodorus reports (XVII.21.6) 2,000 Persian cavalry dead; this is consistent with the mistranslation and misidentification hypothesis: Diodorus is working with a tactical unit half the size of Arrian's tactical unit.)

Then we have between 2,000 to 3,000 Persian cavalry at the Battle of Granicus. This matches our intuitive expectations of a hastily assembled army.

Diodorus reports (XVII.21.6) 20,000 were taken alive; Arrian reports (I.16.6) 1,000 were taken alive. I admit I am at a loss for interpreting this vast discrepency; the best I could offer is that Diodorus's tactical unit for infantry is the Sataba (a "company", 10 of them formed a regiment) whereas Arrian uses hazarabam, and the hazarabam slowly changed its effective size over the course of 170 years.3There is weak archaelogical evidence supporting this hypothesis. Sekunda and Chew cite an article by one A.N. Temerevin published in the Soviet journal Vestnik Drevnei Istorii 151 (1980,1) p.131, but I am unable to locate this journal and have no access to a university library which would contain it. For more on this, see Sekunda and Chew, pages 5–6. This still doesn't explain the anomalous factor of 2 in Diodorus's report, for which I can offer no explanation.

Remark.

I do not claim this interpretation is original, and strongly suspect it's somewhere in the literature (e.g., Murray Dahm's Macedonian Phalangite Vs Persian Warrior: Alexander Confronts the Achaemenids, 334–331 BC may have made this point, or I may have "read it into" the text). In any event, I would cede credit to anyone who has thought of this before, as I am convinced this is not an original thought. (End of Remark)

Persian Army Strength

I would estimate the Persian army consists of 10 squadrons of about 250 cavalry apiece, and 20 units of 300 infantry apiece.4Postulating there were 100 "companies" of infantry (following Diodorus) forming 20 regiments (following Arrian), that would be 5 companies per regiment. The estimated number of infantry per regiment ranges from 256 in a syntagmata, or 72 in a "company" [pentekostys] around this time which yields 360 infantry in a regiment. Taking their geometric mean yields a better order-of-magnitude estimate of 300 infantry in a regiment.

The composition of the infantry consists of Greek mercenaries (presumably peltasts), but also Persian infantry.

If a Persian cavalry squadron formed a wedge, the squadron would consist of 22 rows. If placed next to each other without overlap, this would be no less than 220 yards wide. If there was sufficient space for another squadron between each one deployed (think: squadron, absence, squadron, absence, etc.), then this would be 462 yards wide. I mention this because the Macedonian army should have a comparable "width", or else there would be an obvious flanking problem which is not reported in any ancient text.

Macedonian Army Strength

Arrian is our only source for the deployment of the Macedonian army (I.14.1-3):

[1] Having spoken thus, he [Alexander] sent Parmenio to command upon the left wing, while he led in person on the right. And at the head of the right wing he placed the following officers:—Philotas, son of Parmenio, with the cavalry Companions, the archers, and the Agrianian javelin-men; and Amyntas, son of Arrhabaeus, with the cavalry carrying the long pike, the Paeonians, and the squadron of Socrates, was posted near Philotas. [2] Close to these were posted the Companions who were shield-bearing infantry under the command of Nicanor, son of Parmenio. Next to these the brigade of Perdiccas, son of Orontes, then that of Coenus, son of Polemocrates; then that of Craterus, son of Alexander, and that of Amyntas, son of Andromenes; finally, the men commanded by Philip, son of Amyntas. [3] The first on the left wing were the Thessalian cavalry, commanded by Calas, son of Harpalus; next to these, the cavalry of the Grecian allies, commanded by Philip, son of Menelaus; next to these the Thracians, commanded by Agatho. Close to these were the infantry, the brigades of Craterus, Meleager, and Philip, reaching as far as the centre of the entire line.

I won't bore you with the calculations, but this would describe a battle line about 1346 yards wide (i.e., several times longer than the Persian army, and roughly twice the length of the high ground on the battle field).

For the sake of discussion, we will stipulate this deployment is accurate, and see how far we can go under this (possibly wrong) assumption.

Deployment

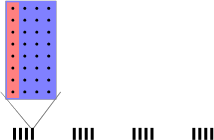

Arrian provides the greatest detail concerning the Macedonian deployment, Diodorus provides the Persian deployment. Arrian (I.14.4) says the Persian infantry was posted along a ride, and the Persian cavalry opposite the Macedonian cavalry. We can draw a map, to scale:

The Order of Battle

The battle of Granicus opens with Alexander leading the cavalry within the right wing of the Macedonian army across the river. The Persian cavalry engages with Alexander (Diodorus XVII.19.5, Arrian I.14). Simultaneously, Parmenion leads the Macedonian cavalry from the left, and engages the cavalry directly opposing him.

The Persian cavalry prevented Alexander's wing from leaving the river, but it's unclear the depth of the river and the steepness of the banks. We are not informed about the Persian cavalry opposing Parmenion's crossing, presumably they likewise tried to prevent Parmenion's crossing.

Persian missile infantry focus on firing upon Alexander's wing of cavalry (Arrian I.15.1).

Independent of all this, the Macedonian infantry crossed the river unimpeded and unopposed. Arrian does not tell us their objective or destination, but did not engage the Persian cavalry (either because they were trying to engage the Persian infantry, or else arrived after the Persian cavalry routed).

The opening movements of the battle could be summed up as:

After fierce fighting, Arrian reports (I.16.1) and Diodorus agrees (XVII.21.4) the death of the Persian satrap ["governor"] and several other [Persian] commanders on the Persian left wing started a route. Then the Persian center routed, followed by the Persian cavalry on the right routed. Last the Persian infantry routed.

The Persian's Greek mercenaries appeared to try a tactical withdrawal, whereas the other infantry broke and fled. The Greek mercenaries were surrounded, fought valiantly, and lost. The surviving Greek mercenaries fighting with the Persians were sent back to Macedonia as slaves.

Why didn't the Macedonians pursue?

The battle thus described raises the obvious question: why didn't Alexander's cavalry pursue the Persian forces?

This is where Arrian's narrative makes more sense. If the battle was fought at the end of the day, then it would be too dark to adequately pursue. However, if this battle was fought in the morning (as Diodorus suggested), then Alexander seems naive.

I've been waffling on which authority is correct regarding the time of the battle, and the more I think about it, the more Arrian's narrative makes military sense.

Analysis

Could the Persians have done anything to avoid (or, at least, improve) their outcome?

Presumably, the Persians were aware that Alexander had a sizeable force, and that they were badly outnumbered. This would be the basis of their strategy to fight at the river, where the Persians believed they would both have the literal high-ground and be able to challenge Macedonian cavalry when the Persians have the advantage [i.e., when the Macedonians are in the river and the Persian cavalry has the relative high ground]. This plan has merit, taking the high ground is always a good heuristic.

But the Macedonians outnumbered the Persians by a factor of 5. It is unclear (and impossible to know) if the Persians were aware of this. Nevertheless, this is the main obstacle the critic needs to confront.

Initially, I thought the Persians should have used chevaux de frise, but this would be anachronistic: they couldn't use something which won't be invented for a millenium.

The next alternative would be to find a superior place to challenge the Macedonians where the terrain will negate any numeric advantages. Sadly, I do not know the area as well as Memnon, so I am forced to assume this is the best feasible location for the battle.

Having made these stipulations, we are left with only one variable left: different deployments. The tactical objective would remain the same (i.e., kill Alexander the Great as quickly as possible). I think if the mercenary hoplites lay on the ground behind the Persian left cavalry, the Persian left cavalry feigned a retreat (and avoided stomping on the mercenary hoplites), the Macedonians would have pursued and found themselves in a tight spot. This is more complicated to execute, far easier to say from the comfort of an armchair.

The only alternatives besides this would be to have a unit or two of the Persian right cavalry be deployed on the left instead, or to deploy mercenary Peltasts on the Persian left. But this is all said with the benefit of hindsight, I know the Persians failed. If I were planning before the battle, would this recommendation still make sense? Probably not the cavalry redeployment, but perhaps the light infantry.

Concluding Remarks

Just from the numbers alone (6000 Persian infantry against 32000 Macedonian infantry, 2500 Persian cavalry against roughly 5000 Macedonian cavalry) it is clear the Persians are at a disadvantage.

A lingering question remains, why does anyone care about this battle that amounted to little more than a cavalry skirmish? I think the answer is two-fold: (a) it is the first battle Alexander the Great fought against Persian forces; and (b) it is a form of ancient propaganda. After carefully studying the literature on this battle, I don't think it's worth the ink spilled over its details.

But it is important because later generals may refer back to this battle in their thinking.

References

- Murray Dahm, Macedonian Phalangite Vs Persian Warrior: Alexander Confronts the Achaemenids, 334–331 BC. Osprey, 2019.

- Donald W. Engels, Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army. University of California Press, 1980.

- N. G. L. Hammond, "The Battle of the Granicus River". The Journal of Hellenic Studies 100 (1980) pp.73-88, doi:10.2307/630733

- Nick Sekunda and Simon Chew, The Persian Army: 560–330B.C. Osprey, 1992.

- Michael Taylor, Antiochus the Great. Pen and Sword Military, 2013.

- Kathleen Toohey, The Battle Tactics of Alexander the Great. Ch.2 The Battle of the Granicus, PhD thesis.