Alexander's Army

Our only source for Alexander's army organization is Diodorus (XVII.17.3-5):

There were found to be, of infantry, twelve thousand Macedonians, seven thousand allies, and five thousand mercenaries, all of whom were under the command of Parmenion. [4] Odrysians, Triballians, and Illyrians accompanied him to the number of seven thousand; and of archers and the so-called Agrianians one thousand, making up a total of thirty-two thousand foot soldiers. Of cavalry there were eighteen hundred Macedonians, commanded by Philotas son of Parmenion; eighteen hundred Thessalians, commanded by Callas son of Harpalus; six hundred from the rest of Greece under the command of Erigyius; and nine hundred Thracian and Paeonian scouts with Cassander in command, making a total of forty-five hundred cavalry. These were the men who crossed with Alexander to Asia.

To tally this in a more succinct fashion:

- Heavy Infantry (24,000)

- 12,000 Macedonian phalangites

- 7,000 Greek ally hoplites

- 5,000 mercenary hoplites

- Light Infantry (8,000)

- 7,000 Odrysians, Triballians, and Illyrians

- 1,000 Agrianians and archers

- Heavy Cavalry (3,600)

- 1,800 Macedonian cavalry

- 1,800 Thessalian cavalry

- Light Cavalry (1,500)

- 600 Greek Ally cavalry

- 900 Thracian and Paeonian scouts

I'm a little confused by Diodorus's arithmetical error with tabulating the cavalry; I guess there's a reason Diodorus became a historian and not a mathematician.

The questions we will try to answer here are: how were these units organized? What formation did they take on the battle field? How were they armed? What tactical roles did they play? How much "space" did they take up? (This last question will be useful when trying to double check ancient estimates of army sizes.)

Infantry

Heavy Infantry

The role heavy infantry played at this time in history is to provide a "solid center". This distinguishes heavy from light infantry, as light infantry plays a complementary role in battle.

When estimating the battle front, we should approximate one heavy infantrymen to be approximately 1 yard per man [0.91 meter]. Marsden's Gaugamela (pg.66) makes this approximation, citing Polybius (XVIII.29.2); Kathleen Toohey's Battle Tactics ch.2 (pg.41) acknowledges this as reasonable.

Macedonian Phalangites

We have discussed Macedonian phalangites before. (Note: the technically correct term would be "pezhetairoi", not phalangite.)

Unlike the Greek hoplite, the phalangite had no breastplate and a smaller shield.

Phalangites were organized into 16-by-16 squares called syntagmata (sometimes translated as "battalion"). Then 6 syntagmata form a taxeis consisting of 1536 infantry, and a variable number of taxeis form a phalanx.

As discussed before, the surissa was much longer than the Greek spear, and as far as using it in combat. Well, Kathleen Toohey refers to this YouTube clip showing what seems like a reasonable deployment (around minute 2 until the end):

Greek Hoplites

We have discussed hoplites before. The critical aspect of a hoplite unit was working as a team, forming a shield line.

The Spartan army had the following organization: A column (literally, a line) of 8 soldiers forms a file, and 4 files form a enomotia ("platoon"). Then 4 enomotiai form a pentekostys ("company"). Then 4 pentekostys form a lochos. There were 7 lochoi in the army. That is to say,

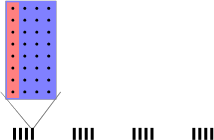

- 1 file = 8 soldiers (highlighted in red below)

- 1 enomotia = 4 files = 32 soldiers (highlighted in blue below)

- 1 pentekostys = 4 enomotiai = 128 soldiers (one group of 4 black rectangles below)

- 1 lochos = 4 pentekostys = 512 soldiers

I think the pentekostys is analogous (in its tactical role) to a phalangite syntagmata, and a lochos is analogous to a taxeis.

Caution: the term "lochos" is used at different times in Ancient Greece for different organizational units (e.g., other ancient authors use it to refer to a "file" in other armies), but Spartan organization has been fairly consistent about consisting of 4 pentekostys. The reader is urged to take care when reading ancient sources if this term appears.

Light Infantry

Light infantry had a variety of roles, usually skirmishing or screening. Unlike heavy infantry, the light infantry were not drawn up in rows and columns: light infantry form a "loose mob", not a rectangle.

The role of ancient light infantry includes protecting the flanks and rear of heavy infantry, as well as using their projectiles either to wound advancing heavy infantry or else get lodged into the shields of heavy infantry (which would be forced to discard the shield or hinder the fighter).

Peltasts

The term "peltast" seems to refer to javelin-armed light infantry, Xenophon explicitly distinguishes Thracian peltasts from Greek peltasts. Their pelte shield carried was smaller than the Hoplite's shield. But the weapons given to peltasts do not seem to be standardized: some carried 2 javelins, others carried spears.

Peltasts defended the flanks and rear of heavy infantry, particular from enemy cavalry. For this reason, mobility is the crucial quality of peltasts in battle.

Cavalry

Remember: stirrups have not yet been invented. All cavalry at this time lacked stirrups.

The roles heavy and light cavalry played, at this time, are just beginning to be distinguished from each other. Thus speaking of "light" or "heavy" cavalry is slightly anachronistic. Squadrons [Gk: ila singular, ilai plural] of companion cavalry were used for scouting, and Thessalian cavalry functioned as shock troops in several battles.

If estimating the dimensions of a horse, Google claims the length of a

horse is 8 feet (or, rounding up, 3 yards). The width that should be

used for a horse is 3 feet, as Kathleen Toohey points out in her discussion of the battle of Granicus [The front occupied by an individual cavalryman should therefore be taken to

have been only three feet

].

For our metric friends, that's a 3 meters length and a 1 meter width.

Heavy Cavalry

Macedonian Cavalry

The Macedonian heavy cavalry, the famous Companions, acted like heavy cavalry and charged into the enemy at speed. How, exactly, this worked without stirrups ensuring the rider won't be unseated, well, it remains unclear (and probably will remain unclear).

Macedonian heavy cavalry fought in wedge formation (a "triangle" or "arrowhead").

Various sources have suggested 200 Companions in a squadron, which (if in wedge formation) would suggest 20 rows drawn up in a triangle. Mathematicians will recognize this is due to the nature of triangular numbers.

Thessalian Cavalry

The role of Thessalian cavalry seems hotly debated. Kathleen Toohey argues they were light cavalry, other scholars argue they were heavy cavalry.

Scholars debate what formation the Thessalian cavalry employed. Extant text from various histories suggest they formed a Lozenge ("diamond") shape. Some scholars argue this was just for training purposes, other scholars point out a lozenge can change direction quickly while retaining the benefits of a wedge.

If the lozenge formation is used, it is likely to have 15-by-15 horse in a squadron (or 225 horse in a squadron), and 8 Thessalian squadrons joined Alexander's army. On the other hand, in a wedge formation, 21 rows would be used (approximately 231 horse in a squadron).

Scholars also debate whether Thessalians were light cavalry or heavy cavalry. This debate, in my mind, is a bit of a "sideshow" since Alexander the Great really introduced "combined tactics". Before now (e.g., at Leuctria), cavalry only engaged with cavalry, infantry only fought infantry. Alexander's battles are literally the dawn of distinguishing "light cavalry" from "heavy cavalry", and Thessalians played both roles throughout the campaigns.

Light Cavalry

Thracian Cavalry

Thracian cavalry (including Odrysians) fought like javelin-armed skirmishers. Armed with 2 javelins (one for throwing, the other for melee) and a sword, scholars believe the Greek cavalry modeled themselves after the Thracians.

Webber's The Thracians (pg 41) and Ashley's The Macedonian Empire (pg 34) argue the Thracian cavalry were organized into wedge formations.

Ashley argues (pg 34) there were 500 Thracians organized into 4 squadrons, which would roughly correspond to the 15th triangular number (i.e., 120 horse organized into 15 rows). Marsden's Gaugamela (pg.38) argues there were 450 Thracians organized into 3 squadrons of 150 cavalry each, which would correspond to the 17th triangular number (i.e., 153 horse organized into 17 rows).

Greek Ally Cavalry

Kathleen Toohey summarizes allied Greek cavalry as being equipped with a helmet, a breastplate, but no shield. For weapons, two javelins (one for throwing, the other for melee acting as a spear) and a sword attached at the belt.

The standard formation for Greek cavalry was a rectangle, not a wedge (nor the exotic lozenge). The 600 Greek cavalry were organized into 5 squadrons [ilai] of 120 horse each. Connolly's Greece and Rome at War (pg 71) suggests they were organized 8 deep ["rows"] and 16 abreast ["columns"].

References

- J.R. Ashley, The Macedonian Empire: The Era of Warfare Under Philip II and Alexander the Great, 359-323 B.C. McFarland, 2004.

- P. Connolly, Greece and Rome at War. Macdonal Phoebus, 1981.

- E.W. Marsden, Campaign of Gaugamela. Liverpool University Press, 1964.

- Rolf Strootman, "Alexander’s Thessalian cavalry". In Proceedings of the Dutch Archaeological Society, 2011. Eprint

- Kathleen Toohey, "The Battle Tactics of Alexander the Great". PhD thesis, revised in 2018.

- Christopher Webber, The Thracians: 700BC–AD46. Osprey press, 2001.

No comments:

Post a Comment